Prosecuting Mass Destruction

Charles Kurzman, “Prosecuting Mass Destruction,” December 30, 2019.

Charles Kurzman, “Prosecuting Mass Destruction,” December 30, 2019.

In early 2018, a small bomb exploded at an intersection in Anderson County, South Carolina. It was hidden in a wicker basket, and when a passer-by opened the lid, the device detonated and injured the man’s leg. Two similar explosives were discovered and destroyed before they could do any damage. The Department of Justice prosecuted the case as illegal use of weapons of mass destruction, and the bomber was sentenced to more than 30 years in prison.

So here’s my question: If these bombs were weapons of mass destruction, then why aren’t high-powered firearms classified as weapons of mass destruction too? The answer has nothing to do with the scale of destructiveness. It involves a Congressional compromise more than half a century ago.

Firearms have caused widespread destruction in the United States – more than 30,000 deaths and 60,000 injuries each year, according to the Centers for Disease Control. In 2018, according to the FBI, four people were murdered with explosives.

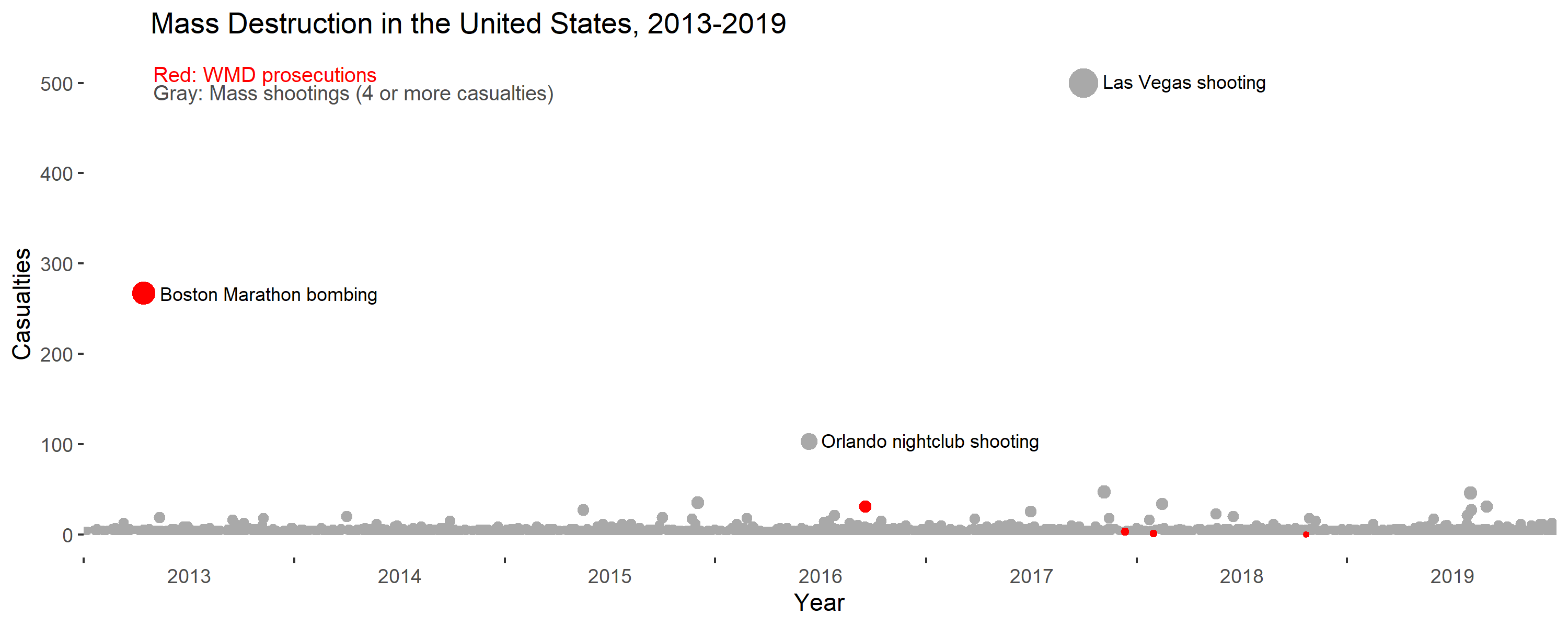

Over the past decade, the Department of Justice has prosecuted 31 cases of weapons of mass destruction, none of them involving attacks with biological, chemical, or nuclear weapons. Most of the cases involved fake explosives provided by undercover FBI employees, but several plots led to actual violence. The deadliest was a bombing in Jerusalem that killed 15 people and injured 122 others. (Six of the victims were American, triggering U.S. jurisdiction.) The Boston Marathon bombing in 2013 claimed three lives and injured more than 200, including 16 people who lost limbs.

Other cases involved no fatalities – the man who placed bombs in the Chelsea district of Manhattan in 2016, injuring 31 people; the bomber who caused three people to suffer ringing ears and headaches in the New York subway in 2017; the man who mailed pipe bombs that failed to detonate to Democratic politicians and other public figures in 2018. These perpetrators were all convicted for using weapons of mass destruction.

Meanwhile, the United States averages a mass shooting per day, using a definition of four or more victims killed or wounded. Fifty-nine people were killed and 441 were wounded in Las Vegas in 2017, the most deadly shooting in recent years. In another mass shooting in 2017, 27 people were killed and 20 were wounded at a church in Sutherland, Texas. A shooting at a school in Parkland, Florida, killed 17 and wounded 17 in 2018. A shooting at a store in El Paso killed 22 and wounded 24 in 2019.

Mass shootings typically involve semi-automatic firearms that are designed to reload mechanically, rather than by hand, and high-capacity magazines that hold dozens of bullets. However, they do not fit the legal definition of a “destructive device,” which includes only firearms with a bore of more than one-half inch in diameter. Most semi-automatic firearms in the United States have a bore of just under one-quarter inch. As a result, tiny explosives count as weapons of mass destruction, just like nuclear weapons, while guns that fire dozens of rounds at a clip do not.

This distinction dates back to 1994, when weapons of mass destruction first entered federal law. That statute relied on an older definition of “destructive devices” that was drafted in 1968, in response to the upheavals of that era. To get any gun control bill passed at all, Congress decided to exempt small-caliber firearms from the category of “destructive devices” – even though small-caliber weapons killed Martin Luther King, Jr., and Robert F. Kennedy, the assassinations that had motivated Congress to bring the legislation to a vote.

What are we to do when the legal definition of mass destruction does not fit the literal definition? One solution would be to use the literal meaning in the application of the law, and refrain from applying the mass-destruction statute to plots that result in relatively few casualties.

Another, more ambitious solution would be to bring the legal definition into line with the literal definition. We could revise the law to include all weapons and accessories, such as high-capacity magazines, that are capable of causing mass destruction.

Very few gun-owners will ever cause mass destruction. Still, many of the guns in Americans’ closets are as dangerous as explosives.