Online Catalogs and the Invisible Heritage of Arab Libraries

I recently received an e-mail from a doctoral student in an Arab country asking to spend a semester as a visiting scholar at my school, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. One of the reasons for the visit, he said, and this has come up frequently in similar letters over the years, is to use our university library. For his dissertation research on his own country, he wrote, there are more resources available at UNC’s library than at libraries in his own country.

We have a great library at UNC, and we are building a serious collection of materials from Arab countries, along with data archives for statistical research and extensive set of American and European materials that focus on Arab countries. But in terms of primary work in Arabic, we have nowhere near the number of volumes held in the major libraries in Arab countries.

What makes UNC’s library attractive to researchers from Arab countries is accessibility, and this is true for any of hundreds of libraries in the United States and elsewhere. Our library’s holdings are visible to researchers through an online catalog. They are aggregated for multilibrary searches through the Worldcat catalog. And they are shared with patrons in other cities through interlibrary borrowing. None of these features, which are taken for granted in the United States, are widely available in Arab countries.

Over the past year, I have worked with colleagues here at UNC and leaders of library professional associations in North America and in Arab countries to gauge the need and prospects for information-sharing and other collaborations between libraries in the two regions, including a survey of Arab librarians. One of the most startling findings of our project was the extent to which library holdings are invisible in Arab countries.

Libraries in Arab countries are custodians of a literary tradition that dates back more than a millennium, including two centuries of printed books. Collectively, these libraries hold more than 50 million items, according to estimates in the Directory of Middle East and North African Libraries. But it is no simple matter to discover which libraries hold which items.

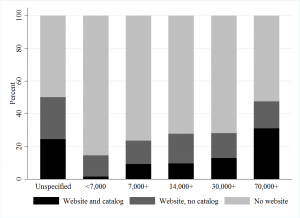

Of the 831 libraries in 17 Arab countries listed in this directory, less than half have functioning websites. Only 15 percent have online catalogs. Even among national libraries, fewer than half offer online catalogs.

Of the 126 libraries with online catalogs, most have to be searched one-by-one. Fewer than half of them — the exact number is unclear — are included in the two major aggregated online catalogs: the Arabic Union Catalog, which is based in Saudi Arabia and focuses on libraries in Arab countries, and Worldcat, which is based in the United States and aggregates catalogs from all over the world. (These two initiatives are linked, so that records from the Arabic Union Catalog are now searchable in Worldcat.) Among the libraries that participate in these interlibrary catalogs, very few list a book’s call number and current shelf availability. Almost no libraries in the region participate in interlibrary borrowing agreements.

Researchers in Arab countries still have to visit libraries one by one during business hours to determine what material is in their collections and then request it. Instead of bringing as much information as possible to patrons via online catalogs and interlibrary borrowing, this system requires patrons to bring themselves to the information.

Over the past year, my colleagues and I convened two conference panels to discuss these issues, bringing together leading library professionals and educators from the Arab Federation for Libraries and Information (AFLI), the Middle East Librarians Association (MELA), and the Special Libraries Association’s Arab Gulf Chapter (SLA-AGC).

One consideration that these experts noted is the need to prioritize preservation over accessibility in many Arab countries. Under uncertain political conditions, with a risk of losing materials to government confiscation or violent conflict, many libraries feel they should keep a low profile. Another consideration is that some libraries prefer to allocate their limited resources to building and maintaining collections rather than investing in high-tech catalogs.

But these experts also stressed that an open stance toward information-sharing may provide a more stable basis for preservation and resource efficiency than the in-house procedures that are currently widespread. Public catalogs allow libraries to identify which materials in their collection are unique and which are widely held, so that preservation efforts and disaster planning can focus on the most valuable items. Partnerships with other libraries, both in Arab countries and elsewhere, can reduce the costs of cataloging and building an online platform — these days, there is no need for libraries to create systems on their own.

In addition to the benefits for libraries, the ultimate beneficiary is the library user. The expansion of aggregated online catalogs and library information-sharing will make more of the Arab heritage accessible to the world. I am happy to have colleagues from Arab countries visit the UNC library, but perhaps, in the future, Arab researchers won’t need to come to North Carolina to access their own written legacy.

[The full report on which this article is based can be found here. More information about the Middle East Library Partnership Project is available here. I thank the Mellon Foundation for its support for this project, my project collaborators Mohamed Hamed and John Martin, the project’s advisory board, and the library professional associations AFLI, MELA, and SLA-AGC for their assistance with this work.]