Crippling International Education

By Charles Kurzman

April 26, 2013

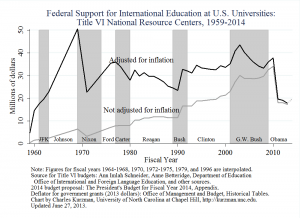

Federal funding for international education has never been so poor. This year’s 5% percent sequestration, on top of a 47% cut in 2011, has brought the Department of Education’s National Resource Centers to their lowest level of support in half a century. (See chart.)

As Congress begins to consider revisions to the Higher Education Act, which expires at the end of this year, it has an opportunity to reinvest in international education. This week, President Obama proposed a 9 percent increase in international education and foreign language studies, but this hardly reverses the cuts this program has suffered.

There are currently 127 centers in this program, which is nicknamed “Title VI” after the section of the Higher Education Act under which it is authorized. These centers are America’s leading source of scholarly expertise on international subjects, helping to produce a significant portion of the nation’s college teachers on international affairs. Two thirds of the professors in my field of Middle East studies got their doctorates at universities with a National Resource Center. (A third of the rest were trained abroad.)

These National Resource Centers subsidize instruction in less-commonly taught languages that is otherwise not financially sustainable. The centers support research and training in every discipline, on every region of the world, leveraging federal funds with state and private money to create the world’s greatest system of international education.

That system is now under threat.

For more than a half-century, this program has had bipartisan support. It was founded by Republican President Dwight Eisenhower, with major expansions under Republicans Richard Nixon and George W. Bush, as well as Democrat Bill Clinton. The last time that the program was in danger, at the end of the Cold War, Republican President George H.W. Bush revived it with a budget increase of more than 30 percent.

Under the Obama administration, however, the program is considered a far lower priority than education programs aimed at helping disadvantaged schoolchildren. Compared with school districts facing shortfalls in property tax revenue, the universities that host these international programs look like fat cats indeed.

But these universities are grappling with budget cuts too, and they are hard pressed to take up the slack when federal matching funds disappear. Many accomplished centers for international education may close.

At the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, for example, we have six National Resource Centers, among the most in the nation. These centers provide seed money for faculty positions, develop new courses on international subjects, and organize hundreds of conferences and workshops each year. Our global education building hums with activity and provides our students with a portal to the world.

This success story was built with federal matching funds, which support up to half the salary of more than a dozen staff positions, folks who teach foreign languages and arrange educational events and manage student fellowships and organize international training for high-school teachers around the state.

These accomplishments are now in danger of being crippled by the cuts to National Resource Center program. The irony in this disaster is that federal funding for these programs is minuscule, less than 1 percent of the Department of Education’s multi-billion dollar budget, which is itself less than 1 percent of the overall federal deficit. Destroying this flagship system of international education will not balance the budget or save our impoverished school districts.

This is hardly the time to scale back on international education. North Carolina and all of America are awakening to a globalized world in which foreign-language skills cannot be left to the vagaries of immigration. Global awareness cannot come simply from the Internet. More than ever, we need serious and high-quality training in world affairs.

This need goes beyond the logic of national security, which was the original rationale for the National Resource Centers (the Higher Education Act was originally called the National Defense Education Act). This need goes beyond the logic of economic globalization, the other major rationale, which views international education in terms of workforce preparation. The greatest need for international education is to promote global understanding in an era when radical movements on all sides are encouraging us to shrink our horizons of empathy.