Who Polices the Police?

Charles Kurzman, “Who Polices the Police?”, October 9, 2020.

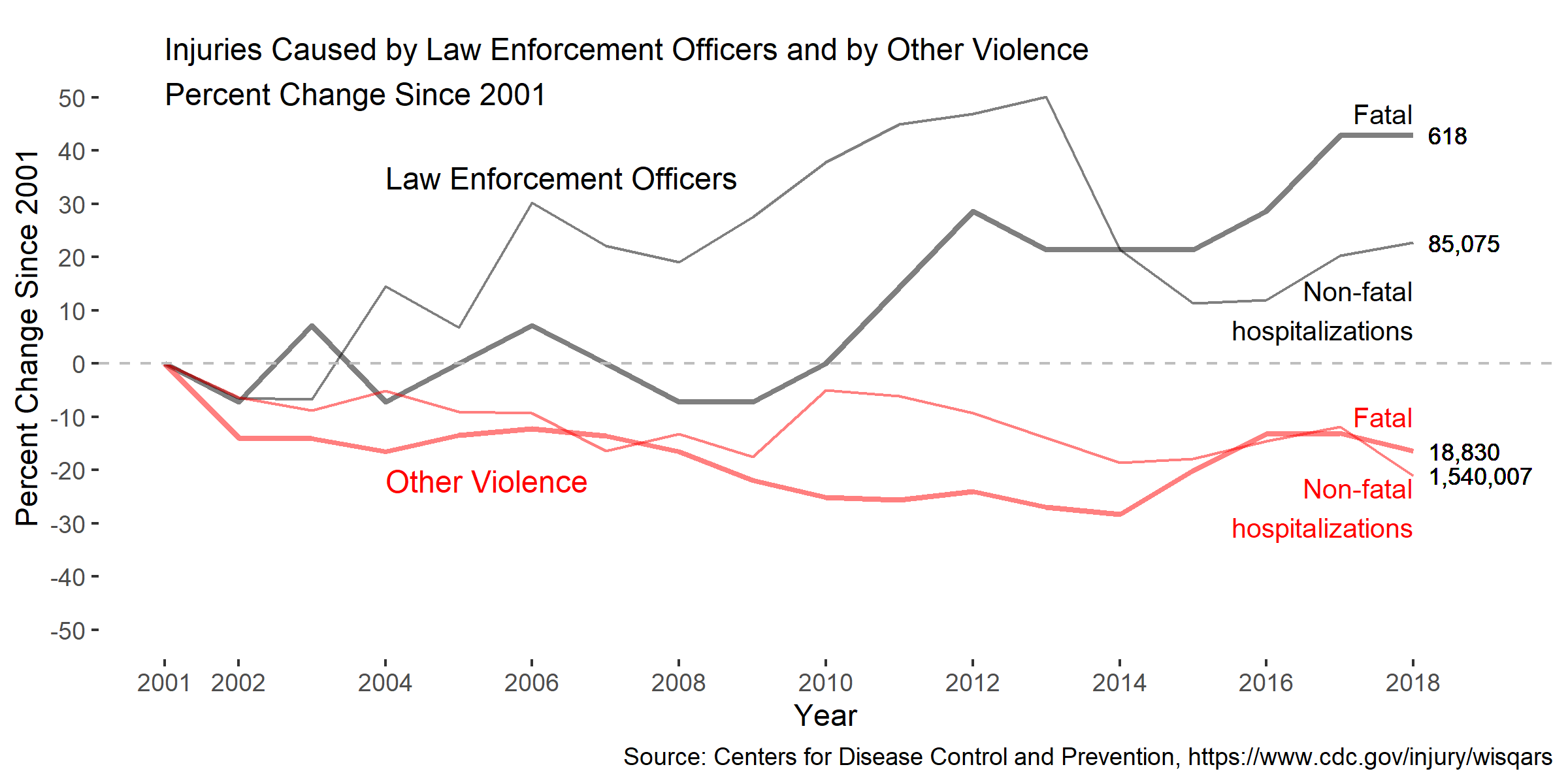

Over the past half-century, numerous efforts at police reform have attempted to bring greater civilian oversight to law enforcement. These reforms have not solved the problem. According to data that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention began collecting in 2001, injuries caused by “legal intervention” have risen in recent years. (“Legal intervention” is defined as “any injury sustained as a result of an encounter with any law enforcement official.”)

As shown in the graph above, deaths caused by law enforcement officers rose 43 percent by 2018, the latest figures available, while other fatal assaults fell by 16 percent. Non-fatal injuries caused by legal intervention – injuries serious enough to require a visit to a hospital emergency department – rose by 23 percent, while hospitalizations caused other non-fatal assaults fell by the same proportion. The rise in injuries from legal interventions rose after the rate for other assaults began falling, so it can’t be credited with reducing violent crime.

The scale of injuries by law enforcement is very small compared with other assaults – about 3 percent of more than 18,000 fatalities and 2 percent of 1.5 million non-fatal assaults in 2018. In addition, it is important to note that law enforcement officers are also victims of violence: 55 officers were feloniously killed in 2018, and more than 18,000 officers – 3 percent of all officers in agencies that reported data – were injured by assaults.

These assaults on law enforcement are tabulated by the Department of Justice and vigorously pursued as serious crimes. By contrast, injuries inflicted by law enforcement are not reported systematically in official data and go almost entirely unpunished. According to news coverage compiled by political scientist Philip Stinson, approximately 200 officers a year are arrested for assault and about 30 a year for manslaughter – less than 1 percent of the number of people hospitalized for injuries from law-enforcement officers and less than 5 percent of fatalities caused by law enforcement.

The disparity between trends in police violence and other forms of violence raises a time-honored question in political philosophy: Who polices the police?

The classic formulation comes from Juvenal, a satirist in ancient Rome, who posed the question as a cynical joke about his wife’s extramarital affairs. “I know the advice my old friends give and their prudent recommendations: ‘Bolt your door and keep her in.’” But this will not work, Juvenal wrote, because “my wily wife” will just bribe the guards. “Quis custodiet ipsos custodes?” he asked. “Who is to guard the guards themselves?”

Over the past several centuries, political philosophy has taken Juvenal’s quip seriously. Samuel von Pufendorf, a German thinker of the 17th century, applied Juvenal to the problem of military coups d’etat: What if the people who are supposed to guard against a coup are themselves the ones who plot a coup?

Josiah Tucker, a Welsh writer in the 18th century, quoted Juvenal in challenging the right of the British monarchy to select its favorites as members of the British parliament. “What kind of guards and centinels will our Representatives become, in watching over the conduct of their own favourites, their own creatures?”

More recently, philosopher John Kleinig cited Juvenal while discussing the accountability of modern police forces. “Juvenal’s much-quoted question displays a deep skepticism toward society’s guardians. Can they be trusted any more than anybody else?”

There tend to be two sorts of answers to this age-old philosophical puzzle: one answer emphasizes virtue, and the other emphasizes law.

Virtue was the answer that Plato gave in The Republic. Authority should be given to “those who have most the character of guardians,” Plato wrote. “They ought to be wise and efficient, and to have a special care of the State.” Candidates for these positions must be tested with “terrors” and “pleasures,” in order to “discover whether they are armed against all enchantments, and of a noble bearing always, good guardians of themselves … such as will be most serviceable to the individual and to the State.”

Thiruvalluvar, an influential thinker in ancient India, also emphasized the importance of virtue: “The enlightened and unblemished in positions of power dare not misuse their privileges to baser ends.”

There is a similar emphasis on virtue in Confucius’s Analects: “To ‘govern’ means to be ‘correct’. If you set an example by being correct yourself, who will dare to be incorrect?”

But philosophers have known since ancient times that not every person in authority is virtuous. In fact, virtue that is strong enough to withstand the temptations of power may be rare.

The Huainanzi, an ancient Chinese text, emphasized this point: “A ruler who desires to govern well does not appear in every age, and a minister who can accompany a ruler in initiating good government does not appear once in ten thousand [officials].” If virtuous leaders are unavailable, “the next best is to correct the laws,” the Huainanzi suggested.

With beneficial rewards to encourage goodness

and fearful punishments to prevent misdeeds,

laws and ordinances corrected above

and the common people submitting below:

These are the branches of government.

Kautilya, in ancient India, also proposed a system of laws – and a network of investigators – to identify and punish officials who couldn’t be counted on to be virtuous:

When government servants commit for the first time such offences as violation of sacred institutions or pickpocketing, they shall have their index finger cut off or shall pay a fine of 54 panas; when for a second time they commit the same, they shall have their ( …… ) cut off or pay a fine of 100 panas; when for a third time, they shall have their right hand cut off or pay a fine of 400 panas; and when for a fourth time, they shall in any way be put to death.

In the modern era, one of the motivating features of democracy was to subordinate powerful officials to the law. As Federalist Paper #51 famously noted, the government of the new United States could not rely on virtue alone:

If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself.

To enable authorities to control themselves, the Constitution set up a system of checks and balances that divided power between different branches of government, and between the states and the federal government. Several generations later, municipalities established modern police forces to professionalize law enforcement with a clearer emphasis on training and supervision.

Yet not all Americans have been guarded against the depredations of the guardians. The history of policing in the United States has long been linked with violence toward African-Americans and poor people of all backgrounds. This summer, massive demonstrations have suggested that the United States needs a different system to protect public safety, including laws that more effectively police the police.

President Trump, by contrast, is emphasizing values. In comments last month that harken back to the themes of ancient philosophy, Trump proposed that law enforcement officials can be trusted to do the right thing because they are good people:

These are great people. These are great, great people. These are brave people. They’re fighting to save people that they never met before, in many cases. And they’re incredible.

Trump acknowledged the need for a legal system to identify and punish officers who lack virtue, and he contended that such a system was already in place:

You have some bad apples. We all know that. And those will be taken care of through the system. And nobody is going to be easy on them either.

But most police violence, he proposed, was the result of good people making honest mistakes under difficult circumstances:

They’re under tremendous pressure. And they may be there for 15 years and have a spotless record. And all of a sudden, they’re faced with a decision. They have a quarter of a second — quarter of a second — to make a decision. And if they make a wrong decision, one way or the other, they’re either dead or they’re in big trouble. And people have to understand that. They choke sometimes.

The important thing, he concluded, was values:

The vast and overwhelming majority of police officers are honorable, courageous, and devoted public servants. They’re incredible.

Trump is relying on the goodness of the guardians to protect the republic. If this position reflects an ancient philosophical theme, it is worth recalling Plato’s warning about guardians who fail to live up these values:

But should they ever acquire homes or lands or moneys of their own, they will become housekeepers and husbandmen instead of guardians, enemies and tyrants instead of allies of the other citizens; hating and being hated, plotting and being plotted against, they will pass their whole life in much greater terror of internal than of external enemies, and the hour of ruin, both to themselves and to the rest of the State, will be at hand.