Q & A on The Missing Martyrs

Selected Q & A with media:

Peter Slen, “Book TV,” C-SPAN2, June 22, 2014 (video).

Rob Sachs, Voice of Russia US, May 24, 2013 (audio).

Frank Stasio, “The State of Things,” WUNC (North Carolina), March 14, 2012 (audio).

British Council, “100 Questions About Islam,” December 10, 2011 (video).

Peter Hart, CounterSpin, November 25, 2011 (audio).

James Protzman, Blue NC, November 13, 2011 (blog).

David Heim, Christian Century, November 10, 2011 (transcript).

Sean Moncrieff, NewsTalk (Ireland), September 26, 2011 (audio).

Eric Felten, “On the Line,” Voice of America, September 16, 2011 (video).

Steve Paulson, “To The Best Of Our Knowledge,” September 11, 2011 (audio).

ThinkProgress.org, September 10, 2011 (video).

Ross Reynolds, KUOW (Seattle), August 30, 2011 (audio).

Steve Malzberg, WOR (New York), August 11, 2011 audio).

Guy Rathbun, KCBX (San Luis Obispo), August 10, 2011 (audio).

Fred Guterl, Scientific American, May 2, 2011 (transcript).

Mike Collins, WFAE (Charlotte), April 8, 2011 (audio).

Diane Rehm, National Public Radio, March 10, 2011 (audio).

Madeleine Brand, Southern California Public Radio, March 8, 2011 (audio).

Robin Young, “Here and Now,” WBUR (Boston), February 9, 2011 (audio).

Selected Q & A with readers:

March 5, 2012:

Question:

I just finished reading your article “Where Are All the Suicide Bombers” in the September/October 2011 issue of Foreign Policy Magazine. There was a statement you made in the article which was thought-provoking, yet at the same time was unsubstantiated in a way which diminished its validity and would/could lead someone to an erroneous conclusion. It was a statement, which could easily be seen as being deliberately used to reach an ideologically predetermined conclusion of a moral equivalence or relativism between two sides in conflict. You made the statement that “a 2006 survey found that 24% of Americans consider attacks on civilians to be justified”. You did not say who conducted the survey, such as Gallup or Pew, and more importantly, you gave absolutely no information as to the nature and context of the question posed in the survey. … I do not think that of the 24% of Americans who responded in the way you state, the majority of them believe that past conflicts in which such tactics were used (World War II, Korea, Vietnam) are reliable examples to use as to how to prosecute the present conflict. Nor do I believe that the majority of this 24% desire to impose unnecessary death and destruction upon an innocent civilian population. Ignoring both of these possibilities implies an American population which is too stupid to understand the nature of the conflict we are in and which has no respect for the sanctity of life in a conflict. We need not get into the weeds about exceptions and outliers into such terms as “respect” and “sanctity”, such as Abu Ghraib, Haditha killings etc.. You well know that in conflicts maintaining “honor” under extreme duress is at best difficult, at worst impossible when we are talking about over 1 million people to have served in theater. It does not mean, however, that we are a fundamentally dishonorable people who mean ill will on innocent others.”

Answer:

The survey I mentioned was conducted by the Program on International Policy Attitudes at the University of Maryland: “Public Opinion in Iran and America on Key International Issues,” January 24, 2007, page 10. I discuss this subject more, with citations, in chapter 2 of my book, The Missing Martyrs. I don’t mean to disparage Americans by reporting these results, and I think that your description of exceptions and outliers who have no respect for the sanctity of life applies to the world’s Muslims as well as it does to Americans.

February 29, 2012:

Question:

What is your view of the critical piece about your work that appeared recently on the website of the Investigative Project on Terrorism?

Answer:

I appreciate the attention to my research and I welcome criticism based on evidence. Some of the points raised by the Investigative Project on Terrorism qualify as evidence-based:

Criticism: My tally of 20 cases of Muslim-Americans indicted for violent terrorist plots in 2011 overlooked one individual, Ulugbek Kodirov, who was arrested for threatening to threatening to kill President Obama.

Response. The correct tally should be 21. Thank you.

Criticism: My list of Islamic statements against terrorism does not delve into the signatories’ views in any detail.

Response: I do that in Chapter 2 of my book, The Missing Martyrs.

Criticism: At a lecture in 2009, I said that Islamic political parties “are generally not wildly popular. The freest elections do not lead to their largest support.”

Response: To avoid giving the impression that I felt qualified to make predictions about future elections, I should have used the past tense, as I did in my writings on the subject: Over the past generation, Islamic political parties have generally not been wildly popular, despite several electoral successes, and the freest elections did not lead to their largest support.

However, most of the Investigative Project’s criticisms are inaccurate. Some examples:

Criticism: The Investigative Project suggests that I should credit government action for the “ebb” in terror plots since 2009.

Response: I’m pleased that the Investigative Project acknowledges this ebb, which contradicts its own inflammatory rhetoric about an ever-growing menace. However, my report frequently refers to law enforcement actions, as well as the environment of “heightened scrutiny” in which would-be terrorists now operate. As I note in the report, this makes the decline in terrorism cases all the more dramatic. In recent years, there have been few plots to disrupt.

Criticism: The Investigative Project writes: “Kurzman does talk about terror financing cases in this report, but does not include them in his chart of terror cases. … Kurzman’s latest report discusses terror financing prosecutions for the first time, but he does not include them in his grid of terror arrests.”

Response: Untrue. Figure 5 of my report charts the decline in terror financing in recent years, and Figure 6 charts the dwindling amounts of money involved in these cases.

Criticism: The Investigative Project suggests that I have downplayed the prevalence of Islamic terrorism in the United States by ignoring foreign nationals: “It doesn’t matter what a person’s passport says. If they are in the United States plotting terror, they are part of the problem.”

Response: I do include foreign nationals plotting terror in the United States in the report, which notes that 70 percent of last year’s suspects, and 68 percent of the suspects since 9/11, were U.S. citizens.

The Investigative Project and I may actually agree on the basic pattern of Islamic terrorism in the United States: terrorism is the work of “fringe elements” who have caused far more fear than casualties in the decade since 9/11. But from there we differ. I encourage Americans to adjust their fear to match the evidence. The Investigative Project, by contrast, calls it “misleading to use raw numbers on an issue like terrorism,” and instead encourages Americans to adjust the evidence to match their fear. The Investigative Project believes that Americans should worry about terrorist violence much more than other, more prevalent forms of violence, such as the country’s 14,000 murders each year. Exaggerating the danger of terrorism in this way serves to “instill mass fear” — the very goal that the Investigative Project attributes to terrorists.

November 28, 2011:

Question:

Joshua Sinai, The Washington Times: What Mr. Kurzman fails to appreciate is that one of the reasons terrorism in the West has become a relatively rare event is the success of the large and expensive resources governments have devoted to countering it. Thus, reports of arrests of terrorism suspects are quite frequent. Once such robust counterterrorism efforts are reduced, per Mr. Kurzman’s recommendation, to end “the state of emergency that limits civil liberties,” the terrorist threat likely will escalate in the West. And after a major terrorist incident, politicians blamed for cutting such resources invariably will end up as ex-politicians.

Answer:

I agree that politicians face a dilemma as they consider bringing our security policies into proportion with the scale of the threat. As I wrote in the conclusion to The Missing Martyrs: “The political calculation for any administration is: how many citizens will change their votes when the next terrorist attacks occur? I don’t know how big this swing vote might be, and how it might be affected by perceptions of government laxity when more competent terrorists eventually surface…” Mr. Sinai suggests that the rarity of Islamic terrorism in the West is due primarily to counterterrorism policies, and not to the factor I document in my book: Muslim communities’ rejection of terrorism. No doubt counterterrorism efforts have saved many lives, as I say in the book. But if Muslim communities were not so committed to non-violence, we would see far more than the 20 Muslim-Americans, on average, who engage in terrorist plots each year, or the 200 per year in Western Europe, with a Muslim population that is roughly five times larger. Ten years since 9/11, we may want to rethink the costs — in finances and liberties — of policies instituted when we feared that the scale of terrorism might be much larger.

November 13, 2011:

Question:

To what extent are events in the Middle East being manipulated by plots like the movie Syriana?

Answer:

There is certainly plenty of corporate and geopolitical skullduggery in the Middle East (and elsewhere), as well as revolutionary conspiracies, but as we’ve seen this year during the “Arab Spring,” popular mobilization sometimes swamps all of the best efforts of the conspirators.

October 14, 2011:

Question:

I was wondering what type of shifts in policy you would recommend after and/or in lieu of a public opinion shift that resulted in substantially less fear of terrorism?

Answer:

I am trying to refrain from offering specific policy changes at this point — I am focusing for now on helping to tone down public paranoia enough that we can have a sensible, evidence-based debate about what policy changes might be appropriate. A solid starting point for that debate would be to disclose more details of our current counterterrorism policies. Two examples:

Is it current policy for agents of the government to engage in radical talk in Muslim communities in order to find Muslim-Americans who might be tempted to engage in violence? How many agents have engaged in this activity over the past 10 years, and how were sites selected for this activity? How many prosecutions and convictions has this activity led to?

How many law-enforcement officials were transferred to counterterrorism duties after 9/11? What duties were they performing prior to that time? Can we estimate how many fewer prosecutions and convictions were achieved in these other areas — securities fraud, for example? — as a result of the reduced staffing?

September 30, 2011:

Question:

Judith Miller, Fox News: [J]ust as the press covers murders rather than traffic fatalities, which far outnumber killings in America each year, it covers terrorism intensively because motive matters. “If it bleeds it leads,” may be a rule-of-thumb in journalism, but how and why the person died still determines the importance of the story. Terrorism is not just run-of-the-mill murder; it attempts to strike at the heart of who and what we are as a nation. And to compare the numbers who died in the deadliest terror strike in our nation’s history with the annual homicides, which occur in all countries and cultures, is to miss the point of what happened in and to America on that fateful day.

Answer:

Yes, motive matters. That’s why we call some violence “terrorism,” and not just “murder.” But there is a downside when journalists cover terrorist motives so “intensively” that they inflate terrorist threats out of all proportion — we may wind up scaring ourselves into panicky policy decisions and a paranoid quality of life. Analogies with traffic fatalities or the annual death toll from murder or other causes of death help give a sense of the actual scale of terrorist threats.

September 29, 2011:

Question:

Fox News: A new online journalism course on Islam appears to downplay the threat posed by global jihad groups, suggesting reporters keep the death toll from Islamic terrorism in “context” by comparing that toll to the number of people killed every year by malaria, HIV/AIDS and other factors. “Jihad is not a leading cause of death in the world,” the online course cautions studying journalists. While that is technically true, researchers at the Culture and Media Institute who examined the online program took exception to that and numerous other claims made in the Poynter News University course. Dan Gainor, vice president at the institute, said the course is sweeping these threats “under the rug,” while watering down the section on jihad with inappropriate comparisons. “Infectious disease, we have government structures to prevent that, and that’s great … in radical Islam we have not even one organization but several organizations that are constantly seeking to kill Americans and others too,” he said. “It seems like journalists should not be involved in trying to downplay that.”

Answer:

I helped to create this online course for journalists, and I am pleased that even a critic of the course acknowledges that it is “technically true” — perhaps that implies that the critique is “technically false”? This critique suggests that acknowledging data on terrorist fatalities (“not a leading cause of death in the world”) means “downplay[ing]” the threat of Islamic revolutionary groups. I disagree. I think that it is important for Americans and the world to know just how dangerous these groups are, so that we can respond appropriately. For readers who are uncomfortable with public-health analogies, a military analogy makes the same point: If a hostile force is large enough to generate massive attacks on the U.S. every year, then we need to protect ourselves with an equally massive response. If it is small and relatively ineffective, then our response should be smaller. Examining the scale of the threat is one of the key elements in designing a defense, and defense strategies constantly seek to update their information on the changing scale of threat. So if Islamic revolutionary groups have not been as successful as we feared they might be, updating our information is not downplaying the threat or sweeping it under the rug — it is recognizing the threat for what it is.

September 11, 2011:

Question:

Bernard Haykel, New York Times Sunday Book Review: While Kurzman’s book is a contribution to the study of Al Qaeda and Islamism, it is a highly selective one. His provocative view that there are so many “missing martyrs” — that there are, indeed, “so few Muslim terrorists” — makes sense only if one concentrates narrowly on the United States and not, for example, on Iraq, Afghanistan or Pakistan. The people of these countries have suffered daily terror attacks in the name of Al Qaeda’s ideology for at least a decade, many of them conducted by suicide bombers, who have been plentiful.

Answer:

Answer:

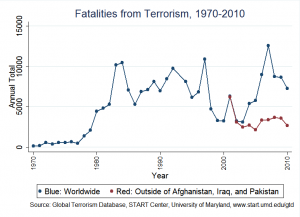

Afghanistan, Iraq, and Pakistan have indeed suffered horrific campaigns of Islamic terrorism, as my book discusses. In fact, these three countries account for a majority of the world’s terrorist attacks since 9/11. Outside of these three countries, the number of fatalities from terrorism worldwide has actually been lower since 2001 than in the years preceding 2001. The chart at left displays data from the Global Terrorism Database maintained by the START Center at the University of Maryland: the blue line shows the annual number of fatalities from terrorism (all sorts, not just Islamic terrorism) and the red line shows the annual number since 2001 outside of Afghanistan, Iraq, and Pakistan. The “missing martyrs” — the waves of Islamic terrorists that failed to materialize after 9/11, as many of us feared they would — are missing not just in the United States, but in most countries of the world.

August 28, 2011:

Question:

Below is my letter reacting to your statements in The Chautauquan Daily regarding Islamic terror. I urge you to subscribe to Jihad Watch and find out for yourself how wrong you are at confusing the public with your misleading statements. …

In his article from August 1st, 2011 entitled: “Kurzman champions discourse on Islam based on facts, not fear,” Kurzman encourages us to base our views of Islamic terrorism on facts not fear. Well, here are some facts. The website http://www.thereligionofpeace.com/ lists the Jihad induced terror and violence all over the world on a weekly basis, and the total such attacks since 9/11/2001 — a staggering figure of 17,560 as of 8/7/2011. These findings are in full contradiction to Kurzman’s message stating that: “If there are more than a billion Muslims in the world and even a small proportion of Muslims were interested in a violent evolution – an attack on the West – we would see terrorism everywhere, everyday. But we don’t.” … There is a reasonable cause for the general public to be fearful of Islamic terror all over the world and there is a need for Kurzman to stop deceiving the public. The more individuals like Kurzman try to conceal the truth about this valid and perilous issue, the more unprepared we are and the more severe the situation becomes.

Answer:

I follow the Jihad Watch and Religion of Peace websites — I have a short commentary on the latter on this page (see Q&A of August 10, 2011) — and I believe that my conclusions are consistent with the data they present. The number of fatalities from Islamic terrorism that they report — and the larger number reported by data from the National Counterterrorism Center — is still, fortunately, small relative to the total amount of violence in the world, notwithstanding the efforts of the terrorists to recruit followers and carry out attacks in Nigeria and elsewhere. I don’t believe that publicizing accurate figures misleads or deceives people, as you suggest. I also reject the idea that to be “prepared” we ought to hide these figures, out of concern that accurate figures do not cause people to sufficiently “fearful” — I believe that our democratic system works best when the people are well-informed, and that includes not just information about terrorist violence but also news about the relative scarcity of terrorist violence.

August 24, 2011:

Question:

I just read an essay in Foreign Policy Magazine (Why Is It So Hard to Find a Suicide Bomber These Days?) adapted from your book, The Missing Martyrs. I really liked how the article points out how Al Qaeda is having problems recruiting because democratic process and semi-peaceful protesting are a more popular vehicle for change among Muslims than Al Qaeda’s out right terrorism. The essay made me think about the 2003 Iraq war, and I’d like to pose a question: Has the 2003 war in Iraq and removal of Saddam Hussein contributed to (or detracted from) the political uprisings we are seeing all over the Middle East? Thank you for considering my question.

Answer:

Thank you for your note. This is an interesting question and worth investigating without political sloganeering. At least one activist in Tunisia cited the overthrow of Saddam Hussein as an inspiration:

“We knew that we could do this when we saw him hang.”

“Who?”

“Saddam. He was the biggest of them all. Bigger than Ben Ali, and bigger than Mubarak. When he was hanging in a Baghdad jail – this brutal and mighty madman – we knew that we could get this done for our people in Tunisia.”

However, surveys from the region suggest that few Arabs are willing to credit Iraq as an inspiration. Professor Shibley Telhami’s Annual Arab Public Opinion Poll, conducted almost every year in six Arab countries, found that only 2% to 6% of respondents felt the 2003 war had benefited Iraqis. Professor Telhami’s most recent survey, in 2010, found no Iraqi leader among the top 12 most-admired leaders outside the respondents’ own country (Turkish prime minister Recep Erdogan was at the head of the list with 20 percent), and the feeling seems to be mutual: Iraqi prime minister Nuri al-Maliki recently denounced the Arab Spring as a Zionist plot. Perhaps participants in the Arab Spring were inspired by Iraqi events and refused to admit it to survey researchers, or even to recognize it consciously — but it would be a methodological challenge to access those sorts of hidden attitudes.

August 10, 2011:

Question:

I was reading some of the background on your book, “The Missing Martyrs: Why There Are So Few Muslim Terrorists”, and I was wondering if you have seen the web site http://www.thereligionofpeace.com which makes some interesting claims that seem to contradict your theory about Muslim terrorists. It is true that in the U.S. they are somewhat ineffective, but in the rest of the world there is Muslim chaos and a lot of deaths. I’m just wondering if the information on this site would sway your opinion.

Answer:

Thank you for your note. I have seen this website – its list of Islamic terrorist attacks (17,572 from 9/11/01 to 8/10/11, with more than 94,000 fatalities) seems plausible, though I can’t vouch for its data. By way of comparison, the National Counterterrorism Center’s list of terrorist incidents of all sorts (not just Islamic terrorism, but including insurgencies in Afghanistan and Iraq) counts more than 77,000 attacks between 1/1/04 and 12/31/10, with 108,000 fatalities (see http://wits.nctc.gov). Both of these datasets show a decline in both attacks (around 20 percent) and fatalities (around 50 percent) from their peak in 2007 to the most recent complete year, 2010. These deadly attacks are still all too frequent. However, they represent only a small proportion of the world’s violence — according to the World Health Organization’s Global Burden of Disease, approximately three quarters of a million people die from violence each year. I present more of this data in my book, and I invite you to read it and see what you make of it. The aspect of the website that bothers me, however, is its insistence that it knows “what Islam is” (for example, on the website’s “Statement on Muslims”, http://www.thereligionofpeace.com/Pages/Statement-on-Muslims.htm). As a social scientist, I don’t think that any religion or any ideology has a single meaning. My method is to examine debates among adherents about what it is. Within Islam, the large majority of adherents abhor the terrorist violence perpetrated by a relatively small number of revolutionaries. (I present a chapter-full of evidence of that in the book, too.) It seems odd to me that anybody would accept an outsider’s reading of Islam’s sacred texts rather than the interpretations presented by Muslims themselves, few of whom accept the terrorists’ views of Islamic duty.

August 4, 2011:

Question:

I am thoroughly enjoying your book but I had to stop reading and ask why there is no definition of ‘terrorism.’ Or have I missed it? And, is it possible to distinguish between terrorism by individuals/groups and states?

Answer:

Thank you for your note. I don’t subscribe to any single definition of terrorism. For a detailed history of debates over the term, I found Ben Saul’s work very interesting, especially his book “Defining Terrorism in International Law,” which addresses controversies over state versus non-state violence.