Syria’s Four Revolutions

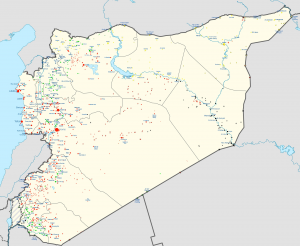

(Click image to enlarge.)

Source: Wikipedia, August 30, 2017.

Red dots: Government control

Green dots: Democratic revolution

Blue dots: Islamic revolution (Nusra Front)

Black dots: Islamic revolution (Islamic State)

Yellow dots: Kurdish revolution

Revolutionary upheaval is not uncommon. Almost a quarter of all countries experienced civil conflict last year.

But it is rare for a country to experience more than one revolution at a time, and almost unprecedented to have four revolutions going at once.

That’s what Syria is going through — four distinct revolutionary movements, often fighting each other as well as the regime of Bashar al-Asad. These revolutions and the government’s brutal response have shattered Syria into bloody shards, with hundreds of thousands of fatalities, millions of refugees, and millions more displaced and suffering.

The world’s attention may have flitted on to other humanitarian disasters, but Syria’s agony continues. How did this happen?

The first of Syria’s current revolutions was a pro-democracy movement, inspired by the overthrow of dictators in Tunisia and Egypt in early 2011. Students rallying peacefully in the southern city of Daraa were arrested and mistreated. Troops shot at crowds demanding their release. Instead of intimidating the opposition, the government’s violence stoked further protest. President al-Asad and his father had tamped down protest for decades through state brutality and a mandatory cult of personality — now, however, democracy looked like it had a chance. Syrians who had previously kept their political preferences to themselves now felt freer to speak out. It was still risky, but no longer seemed futile.

Over the following year, the democratic revolution forced the regime to retreat from parts of Daraa and several other regions of the country. Community groups fashioned makeshift local governments while they waited for the Asad regime to fall. Military advisers from the United States and Europe trained some of its many militias, when it became clear that nonviolent resistance was insufficient to topple the regime. But the regime did not fall.

Instead, a second revolution emerged, one that rejected both the Asad government and the democratic ideals of the “Arab Spring.” This was al-Qaida’s revolution, aiming to install a theocratic state that would enforce its strict interpretation of Islam. Al-Qaida had not previously sought to take territory. Its revolutionary strategy has been based on “raids” — attacks on civilian and government targets that it hoped would trigger violent backlash and ultimately prepare Muslims for a broader revolutionary upheaval. The attacks of 9/11 were part of this strategy.

Al-Qaida’s franchise in Syria, which came to be called the Nusra Front (now the leading group in Hayat Tahrir al-Sham), got permission from al-Qaida’s leaders to try a new strategy: setting up a micro-state in territories that it managed to seize from government and pro-democracy forces. One of the cities the Islamic revolution captured was Raqqa, a regional capital in northeastern Syria.

By the end of 2013, the Nusra Front had lost control of Raqqa to a third revolutionary movement, which at that time called itself the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, or ISIS. This group was originally al-Qaida’s franchise in Iraq. Driven underground in Iraq, it moved next door to Syria and staked its own claim to a mini-state. The following year, the group re-branded itself as the Islamic State, headquarters to a purportedly global caliphate. Al-Qaida rescinded its franchise.

The Islamic State and the Nusra Front both seek Islamic revolutions, but they each consider the other to be unholy deviations from the faith. The Islamic State treats Nusra fighters with the same brutality that it treats other enemies, unless they switch sides and swear loyalty to the Islamic State’s leadership.

Meanwhile, a fourth revolution occupied territory in the far northern strip of Syria. This was an ethnic revolution among the Kurdish minority of the country. The Asad regime had long oppressed the Kurds, banning Kurdish-language schools and Kurdish cultural organizations. Some Kurds aligned with Syria’s pro-democracy revolution, and a few joined the country’s two Islamic revolutions, but the main organizations to emerge in Kurdish communities built an autonomous ethnic enclave, based in the northeastern province of Hasaka.

If the democratic revolution had succeeded in taking power, the Kurdish revolution would have had to decide whether its goal was regional autonomy or complete independence, perhaps in conjunction with Kurdish regions in neighboring countries. So long as the civil wars continue, however, the Kurdish revolution exists in a foggy interim status, technically part of a Syrian state that it does recognize.

The Kurdish revolution has become the favored proxy for the United States and its allies, whose militaries are helping Kurdish forces surround and attack the Islamic State in Raqqa. The offensive is also accompanied by remnants of the democratic revolution, which controls only portions of its former territory in Daraa and northwest Syria.

Much of Syria is now a pointillist patchwork of revolutionary mini-states, sometimes in alliance with one another and sometimes fighting each other.

Four simultaneous revolutions, plus the Asad regime, have destroyed Syria as a unitary nation. It is hard to imagine how the shards will ever be glued back together.