Introducing Powerblindness

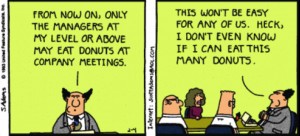

One of the privileges of privilege is obliviousness. We’ve all known people who were born on third base and think they hit a triple – people who ignore or deny the power that they wield, even as they enjoy the benefits. That’s powerblindness.

In a recent paper in the journal Sociology Compass, Rajesh Ghoshal, Kristin Gibson, Clinton Key, Micah Roos, Amber Wells, and I explore this concept and its ramifications. Power and knowledge do not necessarily go together – sometimes the powerful may be unaware of facts of life that the powerless are unable to avoid.

We are hardly the first people to notice this. The oppressed have always noticed.

Even among academics, the insight is not entirely novel. A century and a half ago, John Stuart Mill raised the question, “Was there ever any domination which did not appear natural to those who possessed it?” In recent years, sociologist Patricia Hill Collins has been one of the most influential proponents of this insight. Collins argues that many aspects of power may be “obscured” from the vision of the powerful, but all too clear to the powerless. She offers the example of African-American female domestic workers, who may know far more about their employers’ lives than their employers know about theirs. Maids know their employers’ dirty laundry, and they know they have been hired to clean it.

The concept of powerblindness highlights the cluelessness of employers who forget that their domestic workers are low-wage employees and claim to treat them as “family” – as though they would make family members eat separately, raise their children in poverty, and inherit nothing.

The paper in Sociology Compass identifies five forms of powerblindness:

- – powerblind identity: the failure to notice that one belongs to a privileged group;

– powerblind egalitarianism: the belief that all groups are equal in power;

– powerblind hierarchy: emphasizing one’s own subordinate position instead of one’s power;

– powerblind exception: the claim that one is less privileged than others in one’s group; and

– powerblind justification: the belief that present-day hierarchy is merited or inevitable.

We review evidence for each of these forms, drawing on social-psychological experiments, survey data, and qualitative research.

But we didn’t have to look far afield to locate instances of powerblindness. Teaching Patricia Hill Collins’s work for years has unfortunately not made me any more immune to powerblindness than anyone else.

This was brought home to me several years ago — perhaps I could have seen this coming? – by my family’s housekeeper.

I thought of us as friends. She would share gossip about other people in our community, in a spirit of conspiratorial solidarity. She took my family under her wing when we first arrived in town, after responding to a classified ad for a helping hand. Over the years, she attended family parties — as a guest, not to serve or clean up — and we visited each other’s families in the hospital when someone fell ill.

At the same time, she still cleaned our home sometimes, for pay, so I knew that our relationship was not as egalitarian as I would like friendship to be. I learned just how unequal when she left an unintentional voice-mail message on our home phone. She had called on her cell-phone, without realizing it, while she walked from her car lugging her vacuum cleaner (she said ours was unsatisfactory and insisted on bringing her own). She wasn’t feeling well, and she had to park farther away than usual because I thoughtlessly forgot to move my car, but even so, the stream of profanity that she directed toward my family was eye-opening. She called us filthy, lazy pigs who take advantage of a poor, sick woman, who only cleans up after us because she needs our money.

People of privilege don’t often hear what less privileged people think of them — the “hidden transcript” of the downtrodden, in political scientist James Scott’s phrase. It was disturbing.

I listened to the message several times, first with shock and self-righteous indignation, then with discomfort at the image I had of myself as a benevolent employer and a friend, lulling myself into forgetting my privilege, which she would never forget. That’s powerblindness in a nutshell.