The Rights of Roamers

Many Americans were upset to learn this month that the National Security Agency is recording cellphone conversations in the United States, violating its mandate to operate only outside of the country.

According to an internal agency audit that was leaked to the Washington Post, almost all of these incidents involved what the NSA calls “roamers”: “Roaming incidents occur when valid foreign target selector(s) are active in the U.S. … Roamer incidents are largely unpreventable, even with good target awareness and traffic review, since target travel activities are often unannounced and not easily predicted.”

Debate over the “roamers” has focused on a narrow legal concern: Did the NSA overstep its authority by continuing to record the conversations of foreign targets once they arrived in the United States? The NSA’s chief compliance officer assured reporters that the agency erased the recordings as soon as it identified them as domestic calls.

In other words, the NSA labeled these foreigners as enough of a threat that it recorded their conversations. Then it let them in the country. Then, when the NSA realized they were in the country, it stopped recording their conversations. Really?

This may be an unfair characterization — the NSA could well have passed along these cellphone numbers to the FBI or the Department of Homeland Security, which have their own surveillance programs.

Still, the legal issues notwithstanding, should we be worried about foreign intelligence targets “roaming” around the United States?

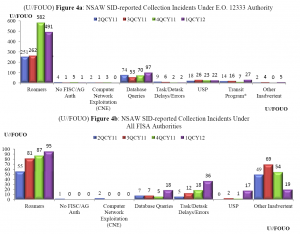

Not too much, actually. The NSA’s audit counted 1,904 “roaming” incidents in a single year (April 2011-March 2012). (See chart above left.) We don’t have leaked documents for other time periods, but there have probably been thousands more “roamers” before and since.

Yet none of these “roamers” has carried out a terrorist attack, and it seems unlikely that any have even been arrested for terrorism-related plots, so far as I can find.

I’ve identified eight individuals charged with terrorism plots – all thwarted in their early stages — who entered the U.S. since the NSA’s major surveillance programs were authorized in 2007, but there is no indication in their indictments that they were targets of NSA surveillance prior to arrival. Four were teenagers with no record of militancy (Khalid Ali-M Aldawsari, Sami Samir Hassoun, Mohammad Hassan Khalid, Quazi Mohammad Rezwanul Ahsan Nafis). Three entered the U.S. as refugees (Waad Ramadan Alwan, Mohanad Shareef Hammadi, Ulugbek Kodirov), and the remaining individual (Amanullah Zazi) entered the U.S. by claiming falsely to be the son of a U.S. citizen – if they had been under NSA surveillance, U.S. immigration procedures would have blocked their applications.

Even if all eight individuals had been wiretapped by the NSA, they constitute a tiny proportion of the “roamers” wandering around the homeland.

As I’ve repeated for several years, terrorism has not turned out to be a leading threat to public safety, despite the recurrence of occasional violence like the Boston Marathon bomb attacks. Americans have been far more likely to fall victim to murder (more than 180,000 since 9/11) and other forms of violence than to terrorist attacks.

“Roamers” have not put a dent in this tally. Literally thousands of them are considered safe enough to be allowed past immigration officials into the United States.

So why are they being targeted for this level of surveillance?

The primary regulation for NSA targeting is Executive Order 11333, issued by President Ronald Reagan in 1981, which authorizes the NSA to engage in “signal intelligence” — basically electronic eavesdropping — to obtain “information constituting foreign intelligence or counterintelligence” (Section 2.3b). Foreign intelligence is then defined, in a circular fashion, as “all activities that agencies within the Intelligence Community are authorized to conduct pursuant to this Order.” (Section 3.4e).

In the years after 9/11, tens of thousands of foreigners were targeted for NSA surveillance, according to a draft report by the agency’s inspector-general that was leaked to the Guardian earlier this summer.

In recent years, we have learned from other leaked documents, new regulations have expanded the NSA’s activities to include metadata information on Americans, not just foreigners. This has caused an uproar in the United States, with rumblings in Congress to rein in the NSA. Civil libertarians are outraged, and the ACLU has filed suit arguing that the U.S. Constitution has been violated.

But this outrage seems to be limited to eavesdropping on Americans, not on foreigners. One leading group, the Electronic Frontier Foundation, has devoted an extensive webpage to NSA Spying on Americans, but the page says nothing about spying on foreigners. The EFF maintains a separate page on international issues with a subpage on mass surveillance technologies, but that page focuses only on the export of surveillance technologies to authoritarian governments. The U.S. government’s own use of surveillance technologies abroad gets a pass.

Surely the United States is not the only country engaged in signal intelligence. But imagine Americans’ outrage if another government were eavesdropping on American domestic conversations the way the NSA does overseas.

This double standard applies not just to signal intelligence but to many forms of foreign intervention. The United States maintains large-scale military installations surrounding potential rivals, such as Russia and China, but will not tolerate foreign military presence near its own borders.

That’s what the Monroe Doctrine declared two centuries ago. Even before the United States was able to project much force overseas, the United States refused to accept rival militaries in the Americas.

That’s what the Cuban Missile Crisis was about — the United States refused to accept Soviet nuclear weapons near American shores, although U.S. had nuclear weapons stationed near Soviet borders.

American law-enforcement engages in a similar double standard. According to United States law, it is legal for American officials to kidnap foreigners on foreign soil and bring them to the U.S. for trial. The Supreme Court affirmed this explicitly in United States v. Verdugo-Urquidez (1990) by concluding that the Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution — which protects “the right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures” — referred only to Americans.

These reflections may seem far afield from the question of cellphone surveillance, but they are all of a piece. The NSA’s “roamers” offer a striking glimpse into actions taken by the United States government overseas that Americans would never tolerate at home. If America wants to stand for rights around the world, let’s start by respecting rights around the world.