Crossword Cosmopolitanism

Charles Kurzman, “What Crossword History Tells Us About the Language We Use,” New York Times, February 7, 2016. “We are more parochial than our grandparents’ generation, according to one indicator: The New York Times Crossword Puzzle. With the permission of Will Shortz, the Times’s puzzle editor, I recently downloaded all of the newspaper’s crosswords, from February 1942, when the puzzle began, through the end of 2015. I created an algorithm to search all 2,092,375 pairs of clues and answers for foreign language words and place names outside the United States.” More…

Charles Kurzman, “What Crossword History Tells Us About the Language We Use,” New York Times, February 7, 2016. “We are more parochial than our grandparents’ generation, according to one indicator: The New York Times Crossword Puzzle. With the permission of Will Shortz, the Times’s puzzle editor, I recently downloaded all of the newspaper’s crosswords, from February 1942, when the puzzle began, through the end of 2015. I created an algorithm to search all 2,092,375 pairs of clues and answers for foreign language words and place names outside the United States.” More…

I want to thank Will Shortz for allowing me to download the data and agreeing to be interviewed, and Jeff Chen and Jim Horne at Xwordinfo for making the puzzle data available.

I also want to thank Josh Katz for the graphics that went along with the article (he and the Times graphics department picked these examples, not me!) and Fred Piscop for the great puzzle that was created for the piece – unfortunately, his name did not appear in the print version of the newspaper.

For those who are interested, here is how I generated the data presented in the article. To identify foreign words, I created a Python dictionary of 2,000 common words in each of four languages — French, Germanan, Italian, and Spanish — and one thousand words in Latin, plus words for seasons, months, days of the week, and numbers 1-20 in various languages, as well as the names and abbreviations of languages (such as “Sp.” and “Ger.”). I removed words that overlap with lists of 5,000 and 18,000 English words.

I then used Python 2.7 to check each word in the crossword puzzle clues and answers for matches in the dictionary, and then hand-coded the results, as well proper-noun objects of prepositional phrases. I don’t think that more sophisticated methods such as topic modeling will work for such short snippets of text, but I encourage others to try.

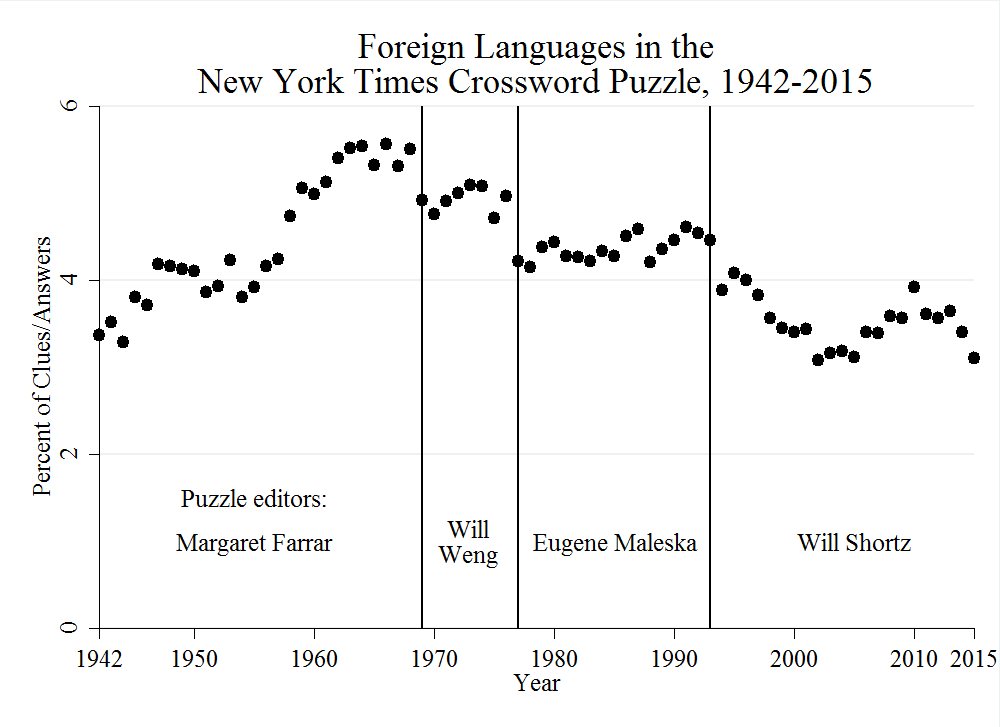

Here are the results, showing small distinct shifts with each new puzzle editor:

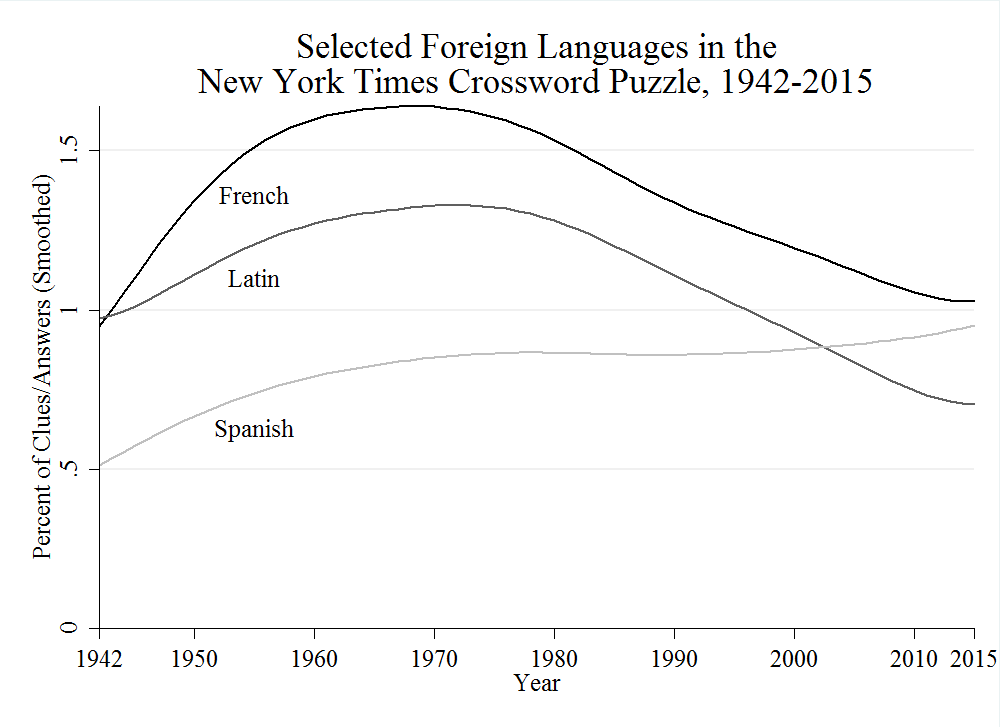

The overall trend is driven largely by the rise and fall of French and Latin, whose appearance in the puzzle was surpassed by Spanish about a decade ago (this graph is smoothed with a Lowess procedure to even out annual fluctuations):

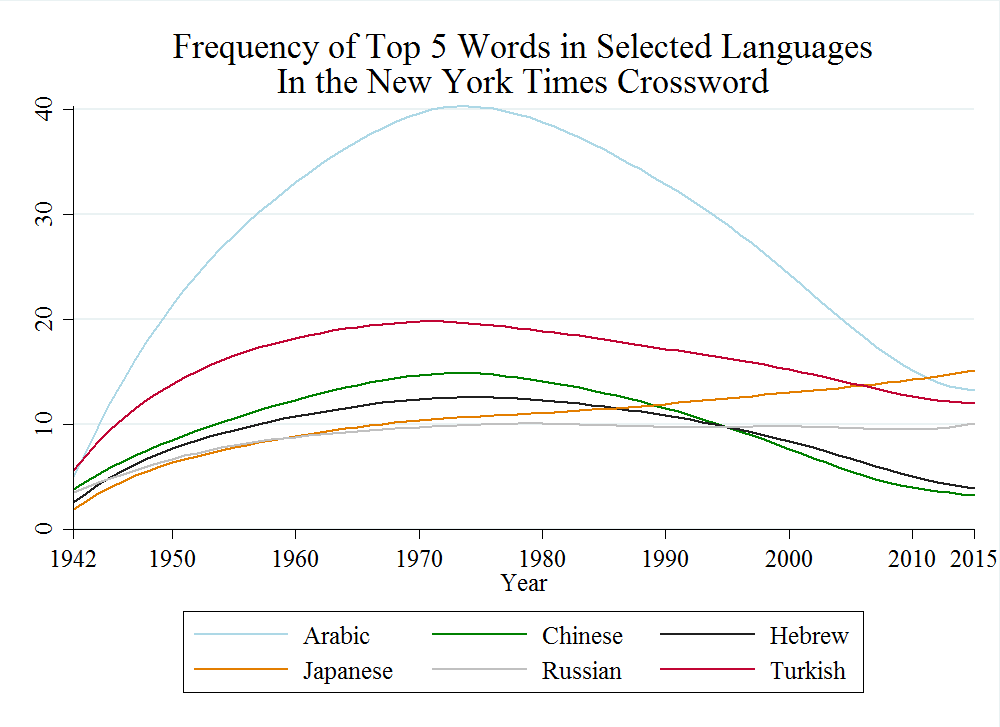

Clearly, the dictionary I used does not include all foreign words. Adding more languages dramatically increased false positives, especially with proper names. But from spot-checks, I don’t think the missing words affect the trends much. Let’s look at the five most common foreign-language words clued as Arabic (aba, abou/abu, alif, ameer/amir/emeer/emir, wadi), Chinese (amah, fantan, sampan, taa, tong), Hebrew (aleph, omer, seder, tav, yom), Japanese (hai, inro, obi, sumo, sushi), Russian (artel, duma, kulak, mir, nyet), and Ottoman/Turkish (aga/agha, asper, imaret, irade, pasha). These words don’t appear very often in the puzzle, and most of them follow the same pattern as my foreign-language dictionary words (smoothed with a Lowess procedure):

Speaking of Arabic, the article should have mentioned the first appearance of Middle Eastern foods, such as pita in 1985 (“Mideastern bread”) – 51 previous usages of pita were related to agave fiber — falafel in 1996 (“Falafel holders”), and hummus in 1997 (“Hummus holder”).

To generate a dictionary of place names, I aggregated lists of world regions, country names, demonyms, the 3,000 largest cities in the world, 140 famous ancient cities, and the 180 longest rivers, then removing places in the U.S.

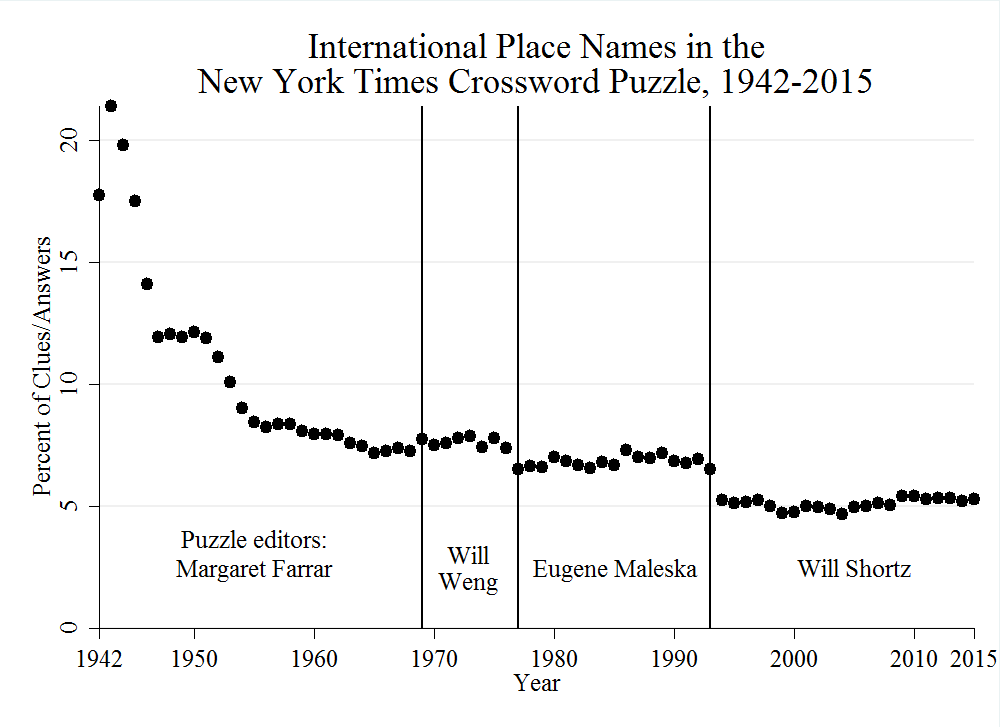

Here are the annual rates of the international place names, again, with slight shifts between each puzzle editor:

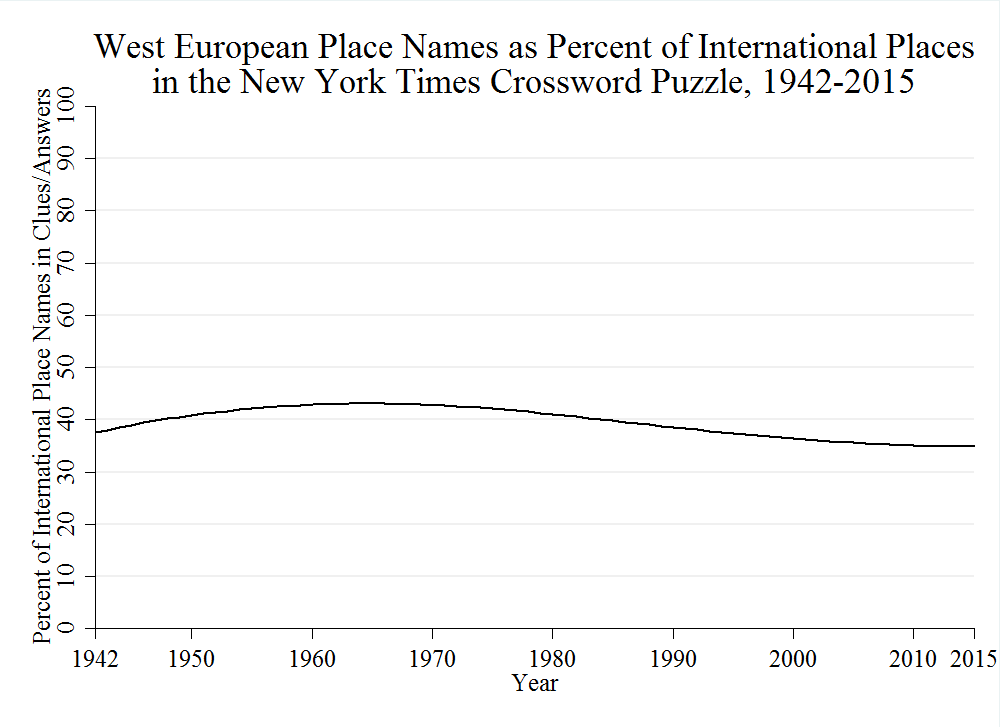

The rate of West European place names (as a percent of all international place names) has declined slightly over the years (smoothed with a Lowess procedure), as shown in this dull graph:

I didn’t try to include counts of foreign people or works of art in the puzzle (although the graphics that were added to the article included some examples of people, such as Friedrich Ebert and Roger Ebert). My hunch is that works by Shakespeare and Verdi would figure prominently.

If someone would like to try, perhaps with research databases such as the Virtual International Authority File (VIAF) for people, Worldcat for books, IMDB for movies, MusicBrainz for music, the Getty Cultural Objects Names Authority (CONA) for works of art, Wikipedia for all sorts of things, and so on. Or perhaps somebody has already aggregated these and more? If so, and you are willing to share, please let me know!