The Meth Vote

Charles Kurzman, “The Meth Vote,” November 29, 2016.

Charles Kurzman, “The Meth Vote,” November 29, 2016.

This fall, the Department of Health and Human Services released its first detailed estimate of the number of methamphetamine users in the United States. The total: 897,000, located disproportionately in small cities and nonmetropolitan areas.

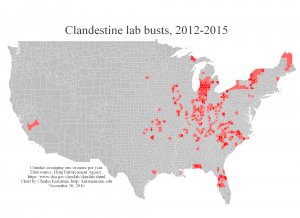

This is Trump country. Counties with the most clandestine drug lab busts — averaging one or more per year since 2012, according to addresses listed online (new address, 2018) by the Drug Enforcement Agency — supported Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton by a margin of more than 2 million votes, according to preliminary returns. Trump lost the popular vote in the rest of the country.

Even in rural areas, meth counties voted for Trump by a margin 9 percent greater than elsewhere.

Meth users and dealers are not numerous enough to make a difference on this scale, and they are not likely to be active voters in any case. In Catawba County, North Carolina, for example, 31 people were arrested for possession or sale of methamphetamines and other Schedule II substances in the month before this fall’s election. Of those, only 11 had ever voted.

But the meth industry is symptomatic of a broader public health crisis that spills over into drug crime, child welfare issues, Hepatitis C infection, and a variety of other problems. As Doug Urland, Catawba County’s health director, told me, “The root level is addiction, and we are still sorely lacking in access to mental health services.”

Across the country, small cities and rural areas are suffering an addiction epidemic. These areas have higher rates of abuse of pain relievers and prescription psychotherapeutics than in big cities, according to the massive 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Depression, thoughts of suicide, and mental illness are more common. CDC statistics show that the overdose fatality rate has tripled since 2000 in small cities and rural areas, surpassing the rate in big cities. Income is lower, according to Census data, as is labor force participation.

Social scientists have already begun to debate which of these factors mattered in the 2016 election. Overdose fatality rates appear to be correlated with county-levels gains in Republican votes, as first reported by sociologist Shannon Monnat. So do indicators of poor health, according to data assembled by The Economist.

Some of the Rust Belt counties that flipped from Democrat to Republican in this election are among the hardest hit by addiction, according to historian Kathleen Frydl.

Much of this trend may also be explained by lower levels of education, as statistician Nate Silver has noted. Outmigration of healthy younger adults might be driving disparities as well.

Also, it is not clear that the election results would have been different if meth counties in swing states had voted for Trump at the rate of comparable non-meth counties, in part because meth labs are concentrated in counties that account for a small portion of the states’ total population.

Still, a partisan meth vote is new. Voters in counties averaging one or more annual drug lab busts in 2004-2007 favored Barack Obama over John McCain by a small margin. In 2012, Obama lost to Mitt Romney by less than a tenth of one percent in counties averaging one or more annual busts in the preceding four years.

The number of lab busts has actually shrunk in recent years. As it has receded from metropolitan areas, meth country looks less and less like the rest of the country. For Clinton supporters who are working on compassion for Trump voters, think of the desperation that might lead people to gamble on a presidential candidate seemingly at odds with small-town values such as honesty, humility, hospitality, and generosity.

If Obamacare is repealed, this gamble may be rewarded with reduced access to substance abuse treatment in parts of the country that need it the most.