Nativism, Then and Now

Charles Kurzman, “Nativism, Then and Now,” March 29, 2018. (PDF version)

America’s current bout of nativism is nothing new. The descendants of immigrants have often opposed additional immigration, characterizing recent arrivals as violent, unpatriotic, unwilling to learn proper English, unable to adapt to customs established by earlier immigrants, a burden on other residents and unfair competition for jobs and resources.

What has changed over the generations is the target of this hostility. One of the founders of the United States, John Jay, suggested “a wall of brass around the country for the exclusion of Catholics.” In the mid-19th century, the Know-Nothing Party organized attacks on German and Irish communities. In the 1880s, mobs destroyed many Chinese neighborhoods. In the early 20th century, eugenicists such as the commissioner of Ellis Island objected to “undesirable and unintelligent people from Southern and Eastern Europe.”

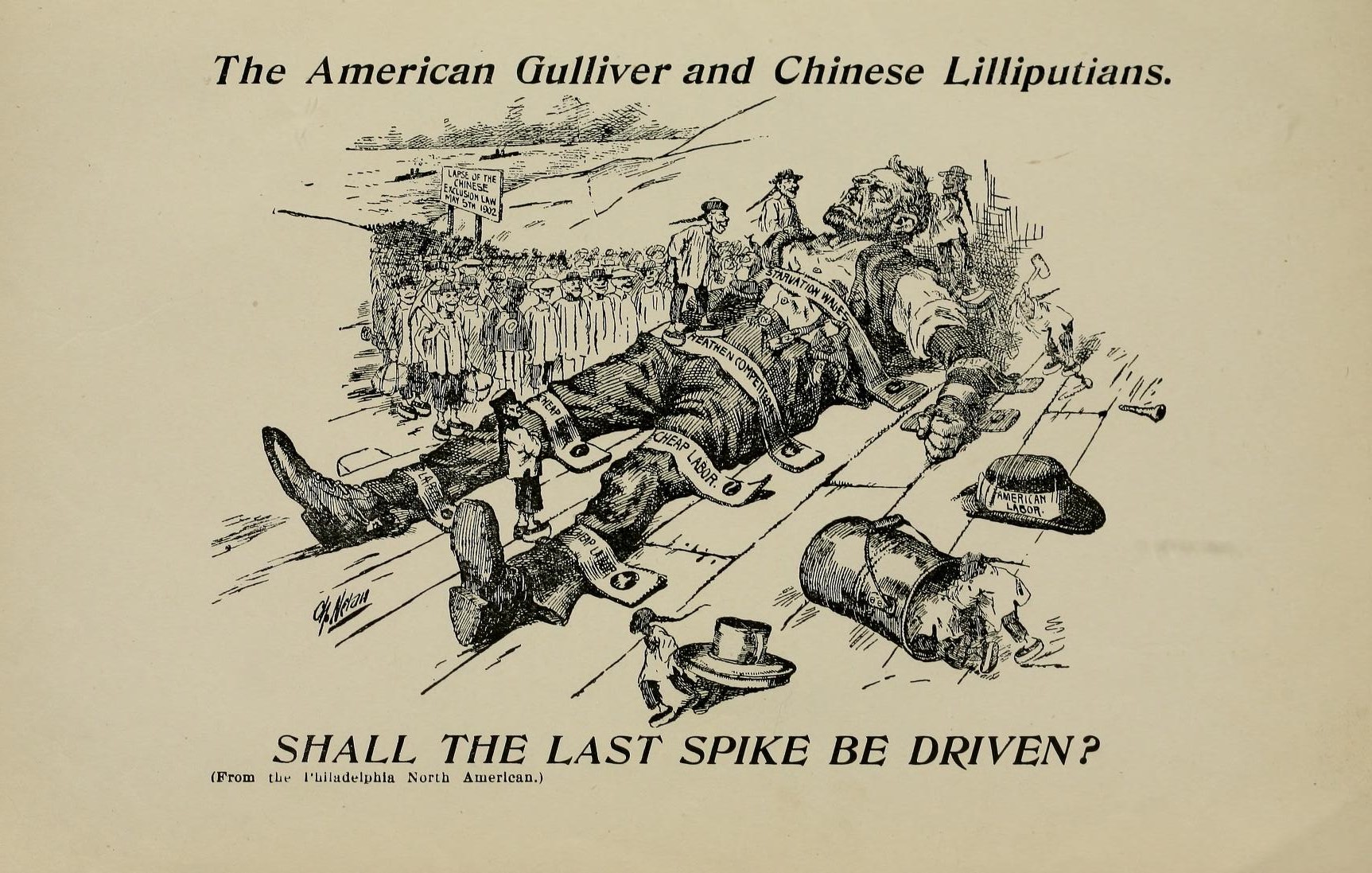

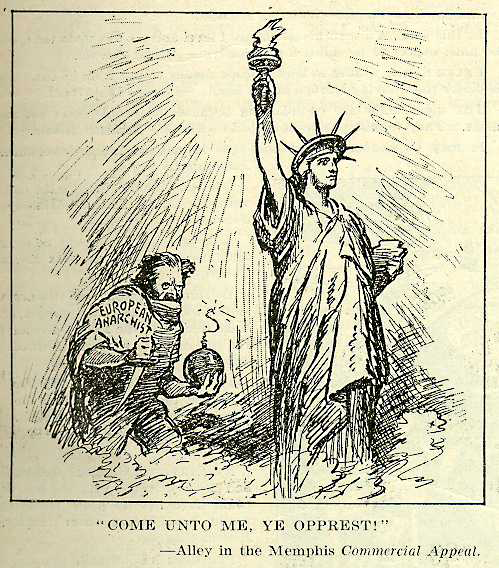

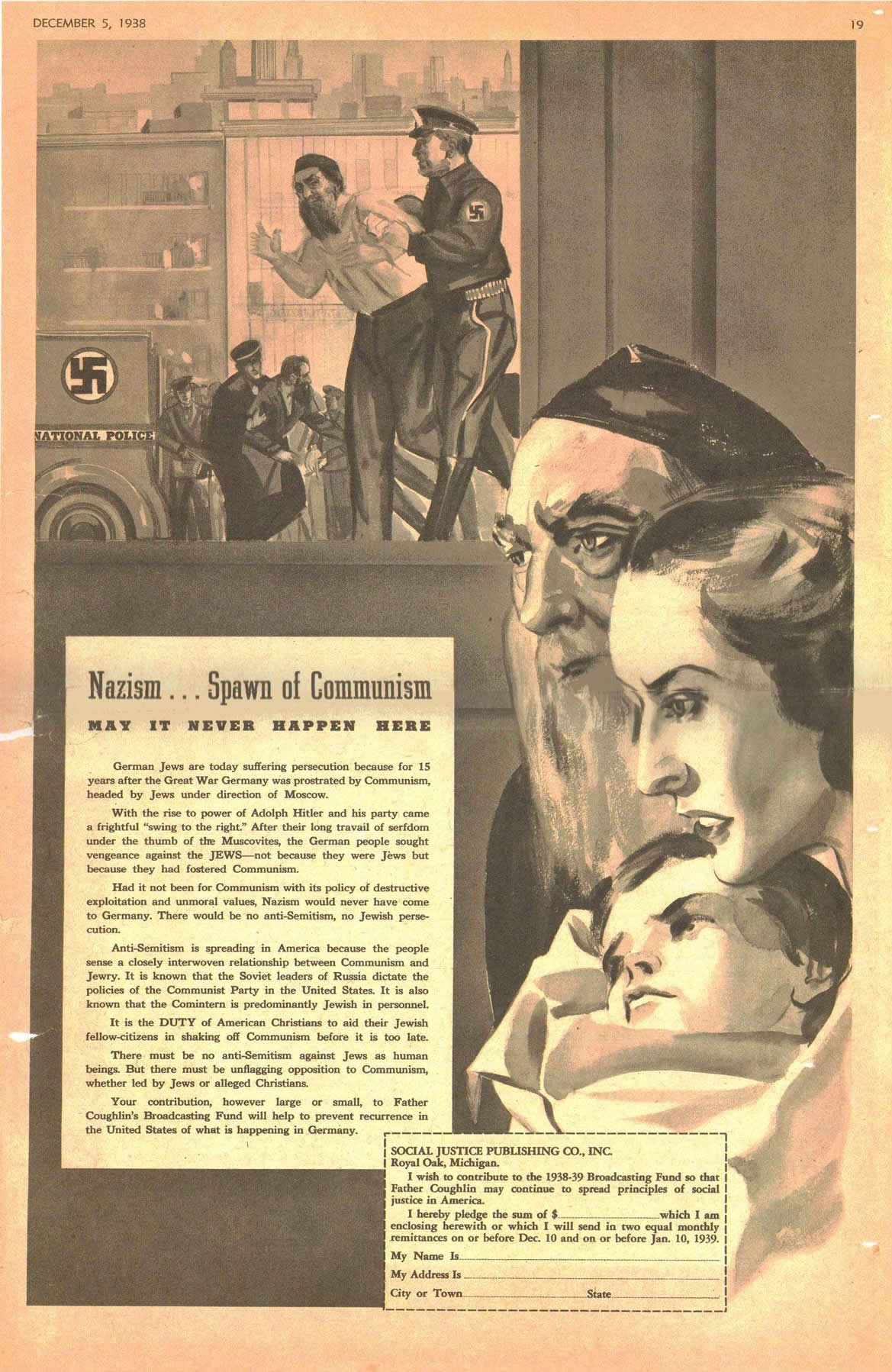

The cartoons pictured below used painfully familiar imagery to depict the Irish as unassimilable, the Chinese as job-stealers, Italians as terrorists, and Jews as communists. Today, President Trump and other nativists aim similar insults at Latin Americans, Muslims, and other immigrants.

Nativists have periodically triumphed, sometimes through legislation and sometimes through violence. But another American tradition has consistently countered the nation’s nativist urges – a tradition that views continual immigration as crucial to American identity and progress. Today’s nativists may need a reminder of the ugly reception that many of their ancestors faced, and of the ideals of openness that benefited their families and themselves.

*

Lady Liberty stirs the “mortar of assimilation” with a spoon labeled “equal rights,” but there is “one element that won’t mix.” This violent character leaps from the peaceable crowd brandishing a knife and the banner of “Clan na Gael” – Clan of the Gaels, a militant Irish immigrant organization. Though mainstream Irish-American organizations repudiated the group’s violence, some Americans – including cartoonist Charles Taylor and the editors of Puck, a leading humor magazine – considered it emblematic of Irish unsuitability for American society.

*

After Chinese workers drove the last spike in America’s transcontinental railroad, Congress banned Chinese immigration for two decades. This cartoon, reprinted by the American Federation of Labor from a Philadelphia newspaper, suggested that the end of the ban would allow masses of Chinese immigrants to subdue white workers with straps labeled “cheap labor,” “starvation wages,” and “heathen competition.” The accompanying pamphlet charged Chinese-Americans with “every crime imaginable,” including smuggling and dealing opioids. Several months later, Congress made the ban permanent.

American Manhood vs. Asiatic Coolieism; Which Shall Survive? (1902)

*

In 1903, a bronze tablet was affixed to the Statue of Liberty with Emma Lazarus’s lines, “Give me your tired, your poor, / Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free…” Some Americans, including editorial cartoonist James P. Alley, considered this an invitation to bomb-throwing anarchists. The previous month, an Italian anarchist group led by Luigi Galleani – who bore some resemblance to Alley’s caricature – had detonated simultaneous explosions in eight American cities, leading to an outburst of anti-Italian hostility and the arrest of thousands of immigrants, most of whom had no connection to terrorism and were later released without charge.

*

As Jews fled Nazi Germany in the 1930s, many Americans objected to refugee resettlement in the United States. Among the most outspoken was Father Charles Coughlin, an influential radio broadcaster. In December 1938, weeks after Kristallnacht, Coughlin’s magazine Social Justice ran a sympathetic sketch of a Jewish man gesturing to his worried family as a Nazi dragged him away. The accompanying text was less sympathetic. Jews had brought persecution upon themselves through their involvement with communism, the magazine suggested, and Americans should also be concerned about the “closely interwoven relationship between Communism and Jewry.” The magazine ominously warned American Jews to “shak[e] off Communism before it is too late.”

*

During his 2016 presidential campaign, Donald Trump often recited “The Snake,” a song recorded a half-century earlier by Al Wilson. The lyrics re-tell Aesop’s ancient fable of a poisonous reptile who cannot help but bite a woman who saved him from freezing, but Trump repurposed the story to insinuate that immigrants were by nature ungrateful and dangerous, especially Mexicans Trump called “rapists,” Syrian refugees and other Muslims he accused of terrorism, and Haitians he claimed had AIDS. At the end of a recent reading, while the audience hooted and cheered, Trump shrugged his shoulders and grimaced, as if to say: What else do you expect?