A Century of Acceleration

Information flies on transcontinental cables. Globalizing markets create massive fortunes, while threatening the livelihood of millions. Crises in remote regions have repercussions across the planet. More and more of us feel pressure to keep up with a world that seems to be racing ahead.

That’s the world in 2016, the “age of accelerations,” according to a new book by Thomas Friedman. But that also describes the world in 1916, the subject of a conference I recently attended in Dublin.

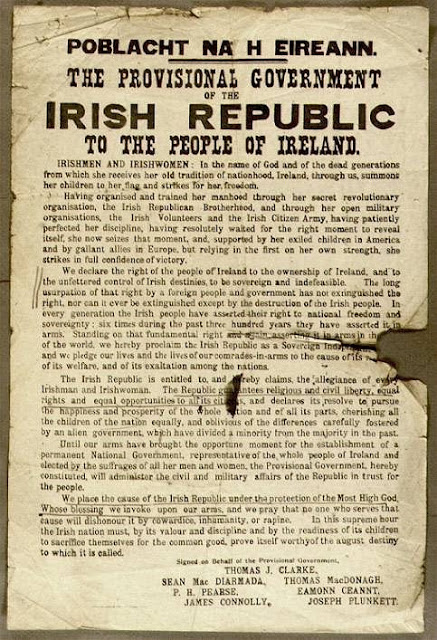

Ireland is currently observing the centennial of the Easter Uprising of 1916, when nationalists rebelled against British rule. Several years later, the country was independent.

This conference focused not on Ireland, specifically, but on the global context of revolutions in an era that historian Mark Jones, the conference organizer, labeled the “age of acceleration.”

Over the preceding half-century, new transportation technologies had begun to move people and things faster than mammals and wind — horses, camels, and sailboats — that had set the speed limit for millennia. An ever-denser network of railroads criss-crossed land masses. Ships driven by steam, then by coal, then by oil sped across the seas, carrying long-distance trade and migrants.

The new transportation technologies were also associated with an unprecedented concentration of global power in a handful of empires. The United Kingdom, France, Russia and the United States — not coincidentally, four of the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council today — ruled almost half of the world’s population, projecting power over thousands of miles via railways and gunships. In 1776, during the American Revolution, British reinforcements reached Boston in six weeks. In 1899, during the Boer Revolution, British reinforcements reached Cape Town in three weeks — twice as far in half the time.

Communications technologies accelerated even more quickly, unleashed from the speed of human travel to travel at the speed of electromagnetism. When Tsar Nicholas II renounced absolute power during the Russian Revolution of 1905, telegraph lines brought the news in time for the next day’s papers in Paris and London. In less than a week, newspapers in Shanghai, Calcutta, and Mexico City reported the announcement.

Ideas circulated along with the news. Chief among these was the idea of the world itself. World’s fairs aspired to represent the cultures of the world. International organizations aspired to mobilize the world. International treaties aspired to regulate the world. We take the world for granted today — love it or hate it — but a century ago it was still a novelty.

This new world was governed by massive inequalities of empire and capital, layered on top of old inequalities of rank and status. But it also inspired visions of equality, such as nationalism, constitutionalism, socialism, and feminism.

The contradiction between vision and reality — between the empire of force and the “empire of liberty,” as Thomas Jefferson termed the spirit of the new era — was obvious to many. “Just look how those Frenchmen talk pretentiously about freedom and equality, all the while seeking world domination like Caesar,” one Ottoman reformer commented, as part of a modernist Islamic movement stretching across Africa and Asia that sought to hold modernity — and Islam — to an egalitarian ideal.

The goal of these modernists, like so many other movements of the era, was to catch up with a world that seemed to be pulling away. “Oh, you stragglers of the caravan of civilization!” one Iranian newspaper lamented. “And oh, you laggards of the road of world progress!” An Iranian reformer wrote in the 1870s: “In this day and age the situation has become such that one must assert one’s presence and keep up with one’s peers. If one shows negligence once, one can fall fifty years behind in one’s affairs.” “Cast a glance around you, and behold how the world has become civilized,” an Iranian preacher railed in 1906.

Today the metrics may be economic growth or sustainable development or the human development index rather than civilization and progress, but the anxiety is similar: We measure our success by the tape of a world that is accelerating year by year.

In the 19th and early 20th century, when global consciousness was just emerging, this anxiety led to revolutionary movements in society after society.

Colonized territories such as Ireland abandoned the dream of equal membership within empire, in favor of national independence. In other countries, such as Meiji Japan, the revolution came from the top. In still others, the revolution came from an intellectual class that demanded constitutional democracy, both as a good in itself and as a mechanism to modernize the state and the society. I’ve written about one such wave of democratic movements — the Russian Revolution of 1905, the Iranian Constitutional Revolution of 1906, the Ottoman Constitutional Revolution of 1908, the Mexican and Portuguese Revolutions of 1910, and the Chinese Revolution of 1910-1911 — in my book, Democracy Denied.

This wave of democratic experiments ultimately failed, undone by frayed alliances and Great Power interventions, but the experience of that era suggests that many of the characteristics of the networked, globalized world order of the early 21st century have a long lineage. In particular, we may identify at least three features that marked the emergence of the world order we are familiar with today:

First, these movements watched one another intensely. One paper at the conference in Dublin quoted a Mexican newspaper quoting a French article by a Russian activist about developments in China — a symbol of the cosmopolitan attention that characterizes the current era.

Second, these movements influenced one another. Revolutionaries in China, for example, sought to learn from the lessons of other world revolutions. “The secret of the strength of Japan and Western countries lies solely in their adoption of constitutional government and convening of parliament,” wrote one influential Chinese intellectual. “This is the trend of history which has greatly changed the mood of the people. Surging waves and rolling waters [of revolution] are engulfing the great earth — a profoundly awesome trend!”

Third, these movements responded to comparable global contexts: massively unequal wealth and power on a global scale, information technologies that made this inequality visible around the world, and ideologies that made this inequality seem intolerable.

These are not new issues. The world has been accelerating for generations.